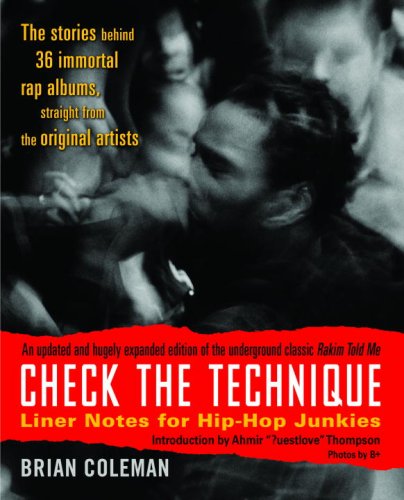

I just found out that Brian Coleman is coming out with a new Hip Hop liner notes book later this year. His first, Rakim Told Me, later re-released under a new name and with additional chapters, Check the Technique are great reads.

The new book looks great. Here's the albums that are covered:

1 - 3rd Bass - The Cactus Album

2 - The Beatnuts - Intoxicated Demons The EP

3 - Black Sheep - A Wolf In Sheep’s Clothing

4 - Company Flow - Funcrusher Plus

5 - The Coup - Steal This Album

6 - Diamond and the Psychotic Neurotics - Stunts, Blunts & Hip Hop

7 - DJ Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince - He’s The DJ, I’m The Rapper

8 - Dr. Octagon - Dr. Octagonecologyst

9 - ED O.G & Da Bulldogs - Life Of A Kid In The Ghetto

10 - Gravediggaz - Niggamortis [aka 6 Feet Deep]

11 - Ice Cube - AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted & Kill At Will

12 - Jeru The Damaja - The Sun Rises In The East

13 - KMD - Black Bastards

14 - Kool G Rap & DJ Polo - Wanted: Dead Or Alive

15 - Kwamé Featuring A New Beginning - The Boy Genius

16 - Lord Finesse & DJ Mike Smooth - Funky Technician

17 - Mantronix - The Album

18 - Masta Ace Incorporated - SlaughtaHouse

19 - Mos Def & Talib Kweli - Are Black Star

20 - Naughty By Nature - Naughty By Nature

21 - Nice & Smooth - Ain’t A Damn Thing Changed

22 - [Chef] Raekwon - Only Built 4 Cuban Linx…

23 - Smif-N-Wessun - Dah Shinin’

24 - Stetsasonic - In Full Gear

25 - Various - Wild Style Breakbeats

Chapter 1 was released with permission on egotripland, but will only be up for a limited time.

Pre-orders through July 25 get the following:3rd Bass — The Cactus Al/bum

The album finally came out in late October of 1989 and went gold within six months. It was enjoyed by fans of all stripes, from hardcore heads to college jocks. It was serious at times but always followed headiness with a good dose of humor or bone-headed fun. Perhaps “The Gas Face” encapsulates what the group was about most effectively: a bouncy, catchy-as-hell beat and funny, loose vocal turns (and an excellent video with more cameos than you can count). But, underneath it all, there is a significant dose of intelligence and honesty about racism and the world in which we were all living, from Far Rockaway, Queens to Johannesburg.

“We honestly never got pigeonholed for being too serious or too goofy,” Serch says. “Our audience and the record label let us do what we wanted. I tell artists today the same thing: ‘Don’t overthink it, just make music.’ That’s what Russell [Simmons] and Lyor [Cohen] told us. ‘Make music and we’ll figure it out.’ We wanted to be goofy, and political and serious. But the one thing we really wanted to be, without question, was dope.”

“It’s a great body of work,” Serch continues. “We were kids enjoying the process of making our first album, and that’s exactly how it sounds.”

Pete says, looking back: “There were just so many different styles on that album, that’s one of the best things about it. It all just flows, from ‘Gas Face’ to ‘Product Of The Environment.’ I’m very proud of that.”

Richie Rich says, “Sonically, they had such an amazing team, with Pete, Sam [Sever], Prince Paul and everyone involved. Musically, that album was just a big step forward. There wasn’t one sample on that record that had been used before, at least not that I know of. They used The Doors, all these rock artists that nobody was thinking of using back then. It opened things up for what was appropriate to be sampled in hip-hop after that. Plus, they were two white dudes who were really rappin’. It was exciting to tour with them, we won people over wherever we went.”

Pete mentions some interesting and monetarily-tempting opportunities they declined back when the album started taking off: “We turned down Sprite commercials because we didn’t want to sell out. Russell and the president of Sony were begging us to accept an offer to be on Beverly Hills 90210. But we thought it was wack. On one level, maybe we should have done some of those types of things. But at the time it seemed crazy.”

Serch makes an interesting point about the timing of the album’s release: “I guess the reason that it took so long is that we just didn’t have the right records until the end. If the album would have come out in 1988 as me and Pete had wanted, I’m not sure how it would have done. We didn’t have ‘The Gas Face’; ‘Steppin’ To The A.M.’; ‘Brooklyn-Queens’; or even the final version of ‘Wordz Of Wizdom.’ Looking back, it’s good that it was delayed a bit. We needed some time to grow and develop as a group. We didn’t see that at the time, of course. But, looking back now, that’s what I see.”

“I wouldn’t want to change anything about The Cactus,” Pete concludes. “It came out exactly as we wanted it to. When we hit gold, there weren’t that many artists with gold records. We never made records to be popular, so to be popular by doing what we wanted was important.”

And aside from some death threats along the way — allegedly from MC Hammer and his brother [see “The Cactus” song comments, below] and some East Coast gang-bangers — along with a couple of C.I.A.-style wire-taps conducted by the duo on their boss, it was all smooth, funky sailing.

Stymie’s Theme

PETE NICE: I put that one together. I was a huge “Little Rascals” fan. A lot of guys our age grew up knowing what that music was. I don’t want to give away too many other samples and get sued, though.

Sons Of 3rd Bass

MC SERCH: The Beastie Boys were huge at the time, and one day I saw Mike D on the street and I ended up talking to him in his apartment after that, because I needed some advice. He gave me really good insight about Russell and gave me some perspective that I really didn’t have at the time. They had gotten out of their Def Jam deal by then. I was leaving his apartment and saying thanks and all of a sudden he just started throwing shit at me, like foam balls and stuff lying around his apartment. I looked at him like he was crazy and I just left. There was no reason for him to do that. Two months later there was a piece in SPIN and the writer asked them what they thought of 3rd Bass or 3 The Hard Way and Mike D said how he threw shit at me and shooed me out or something like that. So that’s where “Sons Of 3rd Bass” came from. I didn’t know any of them before I met Mike that day. That shit he did was really uncalled-for, he was a real asshole. So that’s why I did it. It was like, “I’m going to dis you the best way I can, on wax.” Overall, I thought that there were parts of what the Beasties were doing that were wack. But they weren’t as bad as Hammer.

PETE: By that point, Rick Rubin and the Beasties were off Def Jam, it was a whole different label, really. LL had tanked with [1989’s] Walking With A Panther, so the label was riding on us, Public Enemy and Slick Rick. We felt like we should stand up for the label, but it was more about us being annoyed at the Beasties. Sam Sever was tight with them, so that was weird. And Dante Ross knew them, too. We never thought that song would be a single, we wouldn’t want to be propelled on a dis like that. With the loop on there [Blood, Sweat & Tears’ “Spinning Wheel”], we were playing the song for an executive at Columbia and a guy comes running in the office, asking what we were playing. It was Bobby Colomby, the drummer from Blood, Sweat & Tears, who was an A & R at Columbia. He heard his own song and was freaked out [laughs]. He loved our song, and the sample was cleared. He was just floored hearing our song with his sample, down the hall from his office.

Russell Rush

PETE: I used to secretly record the guys at Def Jam. I did that with all of our meetings, just to hear all the bullshit they would say. That’s where “Russell Rush” came from. That was an actual meeting we had with him. Bill Stephney, Russell and Lyor would tell us all kinds of stuff, and we thought they were just blowing smoke up our asses. So we said, “Fuck it, if they’re going to lie to us, we can at least prove it!” [laughs]. For that episode on the skit, we were in his lawyer’s office, and he’s on speakerphone trying to get a date with Paula Abdul to the American Music Awards. At the same time, we’re all figuring out a new name for the group, because we couldn’t use 3 The Hard Way. That was right when we came up with the name 3rd Bass. At the end of the day, I like the name 3rd Bass. I’m glad we didn’t pick 3 Hard Dicks [laughs].

SERCH: Not too long before the album was coming out, we got a letter from Universal Films saying that we couldn’t use the name 3 The Hard Way. Pete used to record everything, secretly. He’d have a recording thing in his pocket, with a mic attached to his jacket. So Pete recorded the conversation of us going over names with Russell. We also liked 3 Blind Mice and 3 Hard Dicks. But 3rd Bass just made sense. I actually don’t think Russell and Lyor ever caught on to Pete’s secret taping. Pete recorded some very interesting conversations with Lyor, I can’t even remember what they were. The recordings were just so we could say, “We know what you promised us.” When the album came out, I think Russell thought that conversation had taken place in the studio. He didn’t figure out that it was a secret tape.

The Gas Face [Produced by Prince Paul, featuring Zev Love X of KMD]

PRINCE PAUL: The thing I remember most about that song is that I was working on the 4th of July [1989]. Everyone was having barbeques and I was in Calliope Studios doing something on “Gas Face.” That’s when I realized that holidays don’t apply to this line of work [laughs]. I originally recorded the music for that on a 4-track cassette, and what you hear on the final record is transferred from that to a 24-track board. Then we did the vocals in a proper studio, at Calliope. Serch and Pete never came to my spot to record, we were always in a studio somewhere. A lot of people are surprised when I remind them that I produced “The Gas Face.” And no one ever remembers that I did “Brooklyn-Queens” [laughs].

SERCH: I think that was the second-to-last song we recorded for the album. By the time we got to those last two songs, “The Gas Face” and “Steppin’ To The A.M.,” I definitely remember feeling more seasoned in the studio. The funny thing about the lyrics to that song was that I was totally overthinking the process. I was trying to do this connect-the-dots rhyme that was very hard to explain. It wasn’t cohesive and it didn’t sound good on the track. So I was really frustrated. I was listening to the track and that rhyme came into my head: “Black cat is bad luck / Bad guys wear black.” And the rest of that rhyme just flowed out of me. I wrote that verse in the studio. I had worked on the original rhyme for like three hours, and Pete wasn’t feeling it. But then that other rhyme just hit me, and that was it. To be honest, I did not anticipate the reaction that “The Gas Face” got. I remember being really amazed at how much club play it got, the fact that it was thought of as a dance record. That blew me away. I remember we performed in Brixton in the UK, when the Poll Tax was a big thing. And I said, “Black cat is bad luck / Bad guys wear black / Must have been the same Queen / Who set up a poll tax.” And the crowd literally started to riot when I said it. At that point, I understood the global impact it was having. That was a song by a couple of white kids, saying what other white people were scared to say. Many of our counterparts out there were so shocked at the attitude that we had towards the white community. I honestly thought that “Brooklyn-Queens” was going to be the biggest hit off the album. I thought “Steppin’” would be bigger, too, just because it was the lead single and because the beat was so crazy. Plus the Bomb Squad was so hot at the time. “The Gas Face” still gets quoted, I just heard it on ESPN the other day. The cultural significance that record has had is just crazy.

PETE: For “The Gas Face,” we wrote the lyrics to that on the LIR [Long Island Railroad], heading out to see Prince Paul. We had no idea what we were going to do for the song. Zev [Daniel Dumile, aka MF Doom] coined the phrase “Gas Face.” “Steppin’ To The A.M.” was out as a single in May of 1989, so we might have recorded “Gas Face” around that same time. That whole song came together pretty much freestyle. I think there was just something different about that record, maybe because it was Prince Paul. I didn’t know it would be a big hit, though. It was done in one session, one afternoon. All the stuff about Hammer, that was all off the top of the head, none of it was planned. We had a thing against Hammer for sure. In “The Gas Face” song we just said it [dissing him… “What do we think about Hammer?”], but with the video, we expanded on it and that just made it bigger. We didn’t care. If we didn’t like something, we would say it. Everyone was thinking it about Hammer, we just said it.

SERCH: It was simple, Pete and I both thought Hammer was wack, and we both felt that he needed to be called out for it. It wasn’t anything deeper than that. As an MC, I always followed the rule that if you’re going to dis somebody, dis them by name. That’s how I was raised in hip-hop. I didn’t really know any other way. I’m still glad we came out that way, on “The Gas Face” and also “Sons Of 3rd Bass.”

SERCH: KMD [Zev Love X and his younger brother Subroc — Subroc doesn’t rhyme on the song] was on there. I was hanging out in Long Beach for years and years, with our dancers and friends Ahmed and Otis. Doom and Subroc lived down the block. Subroc was the neighborhood barber, he cut everybody’s hair. One of their friends had a Caddy, and we would all chip in five dollars for gas money and go to Roosevelt Field Mall to check out chicks on the weekends, and try to get numbers. When a girl dissed us, Doom started saying “She just gave me the ‘Gas Face.’” Which meant that we just spent our gas money, only to get dissed. The “Gas Face” was when girls would suck their teeth and just walk away. We’d be like, “I could have used that five dollars to buy a hero!” So of course Doom had to be on the record, it was his phrase. They would go on tour with us and then KMD became the first group that we executive produced.

PETE: For the video, I remember we really wanted to get Gilbert Gottfried, and we showed up at the Def Jam offices and he’s there, just lookin’ at us. He didn’t want to say anything, he was so timid. And he was dressed straight out of the ‘70s. We were kinda scared, we didn’t know if he could do it. Then the camera starts rolling and he turns it on and starts going berserk. Bobbito Garcia and Steve Carr, who is a big director now, are the MCs going to sign the contract in the video.

SERCH: We loved working with Lionel Martin, the Vid Kid. He was always able to see our vision and make it happen. He did all the videos on the first album because he’s the only director we wanted to work with. I can’t even say who has my favorite cameo in that video. It’s not even fair. I think that everybody who showed up made it into the video. I love Jam Master Jay smacking the hammer down. Erick Sermon doing the “Gas Face.” All of that was so awesome. Even my man Shake was there, he was a great dancer from around the way. He opened his mouth really wide, like the Predator. It was huge that the whole community came out to support us. I think we only paid Gilbert Gottfried $500 to be in there.

Monte Hall

SERCH: That’s one of my personal favorites, maybe my number one favorite. I would have loved to have seen that as a single. I just think that record is soooo dope. I wrote that about meeting my future wife in a club, so it has extra meaning to me. And I think Pete did a great job with his lyrics, even if he wasn’t in the same space as I was, mentally. That’s a slept-on song, it could have been a huge single. With the reggae stuff going on back then and all the slower-tempo records, it was a great fit.

PETE: Serch definitely wanted a track like that, he was definitely the genesis for that one, lyrically. I had the music for a while and we didn’t know what to do with it. Serch had a lot of great ideas but there was never anything in the middle: it was either great or the worst idea you’ve ever heard in your life. I think it went through a couple bad ideas before we got to that version. I looped it up with Sam.

Oval Office [Produced by The Bomb Squad]

PETE: We definitely learned some things watching the Bomb Squad work. They were so talented, the way they manipulated samples and horns, like they did on “Oval Office.”

SERCH: Working with the Bomb Squad was definitely different. It was a three-headed monster. You’d be in the studio with Eric [“Vietnam” Sadler] and Keith Shocklee, that’s who I spent most of my time with. Eric was the musician type, Keith was there to make sure the lyrics were right. Both of them were on the boards. [Group leader] Hank [Shocklee] would come in during mixing, he’d make sure it was cool, and then he’d leave. He’d nod his head, tinker with something, and leave. I definitely disliked that process and thought that Hank should have been in the studio more. Overall, though, it was cool. I just didn’t know how much Keith and Eric did before we started working with them. I love that song, although if it hadn’t have made the album I wouldn’t have been hugely upset. I mean, it’s just us acting goofy, throwing out double-entendres for the sake of being witty.

Hoods

PETE: That was also from “The Little Rascals,” when the kids are left alone in the house. One of the kids turns on the radio and you hear that scene.

Soul In The Hole

SERCH: I had that song from a while back, it was originally called “Bouncy Bass.” I worked on it with Sam. Pete brought the basketball aspect into it. That changed it a lot, and made it that much better. I definitely like the final version best. The original was a really rough demo, nothing serious.

PETE: “Bouncy Bass” was a cool song, but we wanted to do a basketball-themed song. “Soul In The Hole” definitely had more of a solo feel to it, I guess because it started out that way, with Serch.

Triple Stage Darkness

PETE: That almost has a Bomb Squad feel to it, even though they weren’t involved. “Follow The Leader” [by Eric B. & Rakim] was an inspiration as well. Danceable but chaotic. The sax solo on there was a BT Express song. We did a partial video for that song. I like our lesser-known videos, including that one.

SERCH: That’s one of my favorite songs on the album. I love what Sam did with it. The lyrics are dope, too.

DJ RICHIE RICH: I’m pretty sure that DJ Nite did the cuts on that song.

M.C. Disagree

PETE: That was a recording of our boy Dan, he was childhood friends with Ad Rock from the Beastie Boys. That’s a real message from him, on my answering machine. He went to a club and couldn’t find anyone because he was so drunk. That was pretty funny.

Wordz Of Wizdom

SERCH: That was on our first demo that we shopped. We were still called 3 The Hard Way at the time. That took us like three months to record, I re-did my vocals like 20 times. That’s probably my second favorite track on the album. I love that one. I re-did my lyrics so many times because Pete’s verse was so dope, I didn’t feel like mine matched up. I knew I had to come with something dope. I was fighting my flow, fighting with my verse. After I was working on it for like seven hours, Sam finally said, “You’re not going to get it any better.” And I was like, “Ahhhhh.” I was so mad. But he was right. That song would have been my choice for the first single. In retrospect, I still have no problem with “Steppin’” being first.

PETE: That’s one of my favorite songs. We really wanted that to be the first single, and Russell wanted “Steppin’ To The A.M.” The first verse from the original version of that was pretty much the same as the final. And I think I added my second verse. The original music sampled Depeche Mode [Author’s note: similar to the “(II)” version, included as a bonus on the CD]. When we did the video for that, we had my throne that we debuted in “The Gas Face” again. The concept was just to have the chair everywhere.

Product Of The Environment

PETE: That was a pretty serious song, Serch had that from way back. That and “Wordz Of Wisdom” are my two favorites, just because they go so far back, they were from beginning to end. The music changed from the original to final, but his lyrics were pretty close, if not exact. And I added mine in. When it came to subject matter on the album, I think we were pretty well-rounded. In the press we had a lot of serious articles done on us, so people didn’t see us as goofballs or anything. Marley [Marl] remixed “Product,” it was our fourth single. He changed it all around, his is the version we’d perform live. So it had a second life that way. I like the Marley remix better than the original. We performed that version on the TV show “In Living Color.” Marley’s version was more geared towards live performance. Lionel Martin did the video for that single, too, of course.

SERCH: That was an older one, from me and Sam. The lyrics on there are just my story, how a white kid from Far Rockaway got into hip-hop. That was our fourth single, which was a lot of singles for sure. But it was really a request from DJs and mixers around the country. People loved that song when we were touring, so we put out the single and a video, to extend the album promotion. Pete basically gave Marley the sample that was used on the remix, and Marley freaked it. Marley didn’t want a lot of people to know that, so we let him get the credit, but it was Pete’s sample. We went to see Marley up at WBLS and he said that “Product” was one of his favorite tracks and he wanted to do a remix. We set up a session a week later, Marley flipped it with his horns and the beat. So we went to Russell and said we wanted to do it as a single. I like the remix version better. The original is dope, but the remix is just fire.

RICH: I wanted us to remix a song off the original album, and Marley was playing us beats in the studio. But I felt that he wasn’t diggin’ in the crates as much as he could have been. So I kept pushing him, and he got to that beat [used on the remix]. He had been holding back because I’m sure he wanted to use it for someone else. So we took that one and the horns from the original, and the rest is history. The energy on that remix was amazing, it’s bad-ass from the bottom to the top. That remix and “No Static At All” [from 1991’s Derelicts of Dialect] are my two favorite 3rd Bass songs.

The Cactus

PETE: That’s a Doors sample, we didn’t replay anything. I’m a big Doors fan, so that was my shit. Things just came together in the studio. Sam picked up on it and we just went with it. Then that also became the theme of the album, which was totally unplanned. I can’t even remember how we decided to call it The Cactus Album. I remember having to explain to my mother what “The Cactus” was. That was interesting.

SERCH: There was a lot of drama that resulted from that song, with MC Hammer. The hit [death threat] that Hammer’s brother [Louis Burrell] put out on us was a real concern when we went out there [to LA]. We were in physical danger.

PETE: I’m actually the one who said the line about Hammer in the song [“The Cactus turned Hammer’s mother out”], but Serch took the brunt of it, when Hammer’s brother [allegedly] called up Def Jam. Supposedly he made all kinds of threats, and next thing we’re in LA and Russell told us that Hammer put out the hit.

SERCH: We heard about the threat when we landed in LA, and we were rushed out of the hotel and told to keep our heads down. We thought we were as big as the Beatles, before we found out why they were doing that. They locked down the whole hotel floor, because of a legitimate hit that the Crips had put out on us. Uncle Mel was our security guard at the time, but Mike Concepcion, who was the leader of the Crips, brought in this guy Pookie to roll with us. He was a lieutenant who was well-known throughout California. So if anyone tried to do anything, Pookie would be like, “It’s off.” We were out there for like four days, and we had a thing at KDAY where we were interviewed and they had Hammer call in. That was on the second day. I was beyond pissed at [KDAY DJ and Music Director] Greg Mack about that, I told him to go fuck himself. But I couldn’t knock it, it was great radio. I turned it around on Greg and said, “Why don’t you ask people out there who is doper, 3rd Bass or Hammer?” And it was overwhelming for 3rd Bass when people called in. But he edited it so that it was even. I called Greg out on the air, saying that Hammer was his boy. Then he took a live call on the air from some Crips, who were like, “Yo, we’re coming to kill you.” At that point, we were outta there. KDAY was on a dirt hill, and there was only one way up. So after that call on the air, we were in our van on the way down, and there was a low-rider at the bottom of the hill. Guys came out with sawed-off shotguns and AKs and Pookie had to get out and wave his sign, telling them it was off. Then those guys drove away. So, it was real. We had to sneak into our own album party, as security. All our shows were cancelled except one at the Palace, our album release party. Once I saw Eazy-E, Dr. Dre and N.W.A. there, though, I felt better. To call the hit off, I think that Russell had to give Mike Concepcion two tickets to the American Music Awards, sitting next to Michael Jackson. If you look at the tape of the Awards, you’ll see a guy in a wheelchair sitting next to Michael. The president of Columbia Records had to give up his tickets for that.

PETE: I remember going to KDAY in the morning and they were looking for snipers up in the hills. We were on the air with Greg Mack and he blindsided us and put Hammer on the air with us, live. I have a tape of it somewhere. We argued a bit, we were pretty displeased that Greg Mack did that. We had other shit like that. Once, in Maryland we had to be escorted by State Police because it was rumored that there was an initiation for a local gang to kill one of the members of 3rd Bass. So we had escorts at the venue and then to the state line. That was before the Hammer stuff in LA. The guy in LA who was the godfather of the gangs out there was Mike Concepcion. We had to meet with him, Russell interceded to squash the whole thing. It wasn’t a joke, it was real. And the Hammer thing is just one line in the song! It was crazy.

RICH: That shit in LA was definitely real! But I was 19 or 20 at the time. I had a knife with me and I thought I was OK. Right now, if I had to go through the same thing I’d probably be worried. But at 19, I wasn’t scared. I thought I could beat up 10 people in a bar fight [laughs].

Flippin’ Off The Wall Like Lucy Ball

PETE: That was a Tom Waits sample [“Way Down In The Hole”]. I looped it up with Sam and was thinking about running it in one of the other songs. We were just playing it and Serch heard it and wanted to mess with it. He just started going nuts and we just pieced it into the song. It was hysterical. He was completely sober when he did it. The group of people we had in the studio was dope, we had so much goofy shit, so many inside jokes. That wasn’t something we were planning to include on the album, but after we did it, we had to. After all that, we ended up getting sued by Tom Waits.

SERCH: I wasn’t drunk for that, I swear. I wasn’t under the influence of anything at the time. We were in-between recordings and [engineer] Kevin Reynolds and I were just bugging out in the studio. Sam had this Tom Waits sample and he was playing with it, and I said, “That sounds like some country bumpkin’ shit!” and I started doing that voice. Everybody was laughing so I was like, “Yo, let’s record it and see what comes out of it.” It was pretty much one take, there might be one edit in there that we did on purpose. There was no debate about putting it on the album, but later on we found out through his attorney that Tom Waits thought we were insulting him with my vocals. So he sued us, and won. I didn’t know anything about Tom Waits at the time, I was just doing that voice. I thought we had cleared that sample, but obviously we hadn’t.

Brooklyn-Queens [Produced by Prince Paul]

PETE: That was the other Prince Paul production on the record. The theme of the song is something I had with Blake [Lethem, aka Lord Scotch]. The old version was what we were going to record and put out with Richlen [Productions] back in 1987, before Blake disappeared. We even did a demo of it at Funky Slice, on some programmed beats. I remember Paul gave us a cassette with eight tracks on it and we picked out the music for “The Gas Face” and “Brooklyn-Queens.” Blake had disappeared, so we just did it [as 3rd Bass]. I heard that Blake saw the video for that song when he was at Riker’s Island, I’m not sure why he was in there. We hadn’t even developed that song too far with Blake, it’s not like Serch was saying Blake’s lines or anything. We recorded “Brooklyn-Queens” and “The Gas Face” within a week of each other, in 1989. It might have even been the same day. That was a cool video, the ideas for videos were always ours. One of the Hasidic guys in the video was this guy MC Reanimator. He went to grammar school with Blake. It was cool to throw the Jackie Robinson quotes in the video, too.

RICH: That was the title of a song that me and Pete had worked on at Funky Slice in 1987. I don’t think Blake was on the version I’m talking about. It was only a demo.

SERCH: I had liked that song we sampled on there [“Best Of My Love” by The Emotions] for a while. Then Pete started talking about “Brooklyn Queens” and I said, “Aw, that is so dope!” It was just such a great play on words. And we just built it from there. There’s not much of a story behind it, except that it was one of the fastest songs we actually recorded. It was a different Paul session than “The Gas Face,” I think we did it at Greene Street Studios. “The Gas Face” was at the place Paul used in Long Island [Island Media Studios]. By the time that single was out [in 1990], we were poppin’, we already had two popular singles on the street. So we had a whole different swagger when we did that video.

Steppin’ To The A.M. [Produced by The Bomb Squad]

SERCH: That was the very last song we recorded for the album. I had originally written my verses on that song for Rakim. I guess Rakim and Eric B. had gotten into a slump on their second album and Lyor asked if I would write a song for Rakim. So that song was written with him in mind. It wasn’t really that daunting, I just saw it as an opportunity to write for one of the greatest MCs of all time, even if what I was writing was only going to maybe be inspiration for him. So, Lyor set up a conference call with me, Pete and Eric B. I started rhyming the song and Eric B. hangs up the phone and calls Lyor directly, and starts flipping out on him. Lyor was heated and he comes downstairs and asked why I didn’t tell him that I had beef with Eric B.! And I said I didn’t. I think Eric just couldn’t believe I would have the audacity to write for Rakim. Eric hadn’t asked for me to do it, it had been Lyor’s idea. It took about two months for that single to break out, which seemed like an eternity to us. At the time, Def Jam was starting to give up on the group and they thought maybe we could make something happen in Europe. There was more excitement about us over there. So, in the U.S. they hadn’t released the single yet. We were over there in Europe when we got a fax saying we had done 25,000 units our first week. When we got back to the U.S., I was in a limo and they put on Kiss 98.7 FM and they introduced the song as the hottest record in New York. It was on and poppin’ after that. I attribute the single’s success to Wes Johnson and the promo staff at Def Jam, they didn’t give up on the record. Bobbito supported it, he was our boy. I think if we were just another act, we would have had our two month cycle and then Def Jam would have been on to the next. But people at the label genuinely loved us. We realized that we had sampled the Beastie Boys on there [saying “What’s the time?”], but we didn’t care. It’s a great sample, it works perfectly.

RICH: That song was always tough for me to DJ live, because Serch would bust out dancing and the whole stage would be shaking. It got to the point where I would have to pick up my turntable when he was about to do the Roger Rabbit, or it would skip all over the place. With that song and “The Gas Face,” Serch would get down.

PETE: That single came out in May 1989 and we got played on mix-shows, because we knew everyone. But it wasn’t in any kind of regular rotation yet. I think the video budget for that song was $20,000 or $25,000. We hired Lionel Martin, The Vid Kid, who was part of Video Music Box. That was a big thing. We originally wanted Lionel because he did “Night Of The Living Baseheads” for Public Enemy, and he did editing stuff with stopping and starting and interludes. At that time, videos were still kinda new to hip-hop, they weren’t central to everything. Once the video hit on Video Music Box, sales definitely went nuts. We had released the 12-inch and it was doing all right. We opened for De La Soul in Manchester or Brixton in England, and it was cool. But that’s when the video came out, and then the numbers started blowing up. Daddy Rich became our main DJ but for the video, DJ Nite is in there. We didn’t really know that was going to be a single when it was recorded, but Russell paid the money to bring in The Bomb Squad, so it all fell into place. He really wanted them. We couldn’t do more than two songs with The Bomb Squad because we couldn’t afford it! But working with The Bomb Squad also meant that Def Jam was willing to put money into us, because Hank Shocklee wasn’t free at the time. Even though they produced it, some of the musical ideas were ours. I brought the time sounds. Keith [Shocklee] found the horns. That song was pretty outlandish, all the sounds and everything. I originally envisioned them giving us a harder song, but it was great. We sampled the Beastie Boys on there [MCA saying “What’s the time?”]. Keith threw that in. Def Jam owned the masters, so it was easy to clear. It never came up [that they dissed the Beasties on “Sons Of 3rd Bass” and also sampled them on the same album], which is surprising, now that you mention it.

Who’s On Third

PETE: Daddy Rich did the cuts on that one, definitely. That was just a beat we put together.

Wordz Of Wizdom (II) [CD only]

PETE: That was my original music for that song, but the extra breakdowns on that version were added. My original was just in demo form, with the Depeche Mode sample. But we went a little nuts on all the extra stuff, the drops and everything. We still liked that old version but obviously we liked the new one [which is further up in the album sequence] more. The “II” version was only on the CD, not the LP or cassette.

SERCH: That was just a hidden treat that we wanted to give the fans.

- Autographed copy of “Check the Technique Volume 2” book

- Book arrival to pre-sale participants several weeks ahead of any retail availability (September 2014)

- Exclusive Smif-N-Wessun “Home Sweet Home” big-hole 7-inch, with color picture sleeve and instrumental on b-side. This 7-inch will never be available for retail purchase, it can only be obtained via this pre-sale.

- $29.98 plus postage / handling

http://www.getondown.com/product/item.php?id=17495" onclick="window.open(this.href);return false;